Structured content is the most important trend in digital marketing that you’ve probably never heard of.

Of all the stories and advice in our book Outside-In Marketing: Using Big Data to Guide Your Content Marketing, the one that has attracted the most questions from my colleagues is the section on structured content. By structured content, we mean small content modules that are tagged for use by different devices, applications, or media types.

Structured content is fast emerging as a necessity for content marketers for a variety of reasons, including search, reuse, and content merchandising applications. The main reason for structured content is adaptive content strategy; meaning, different devices need to display different content depending on the use case. It’s not enough to code your pages as Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP), per Google’s specs. Though important, AMP pages just improve load times for your mobile users. You also have to deliver on the promise of offering different experiences to your users depending on the device. That means not just responsive design, but adaptive content.

You might have noticed that mobile users have high abandonment rates on your content and wondered why. Perhaps you have already spent a bunch of money making your site responsive, with little success. All that did was change the shape of the content. If it was built for the PC, that means users on a phone are forced to scroll, and scroll, and scroll some more for the content they need. If the answer to the query that brought them to your content is not in the first screen, most will bounce. The answer might be above the fold for a PC and three screens down on a phone. That won’t cut it.

The solution to your problem is adaptive content–content that can change in ways beyond its shape: different paragraph order, sentence structure, or even word order are all possible with structured content. And you can test each variation with live users.

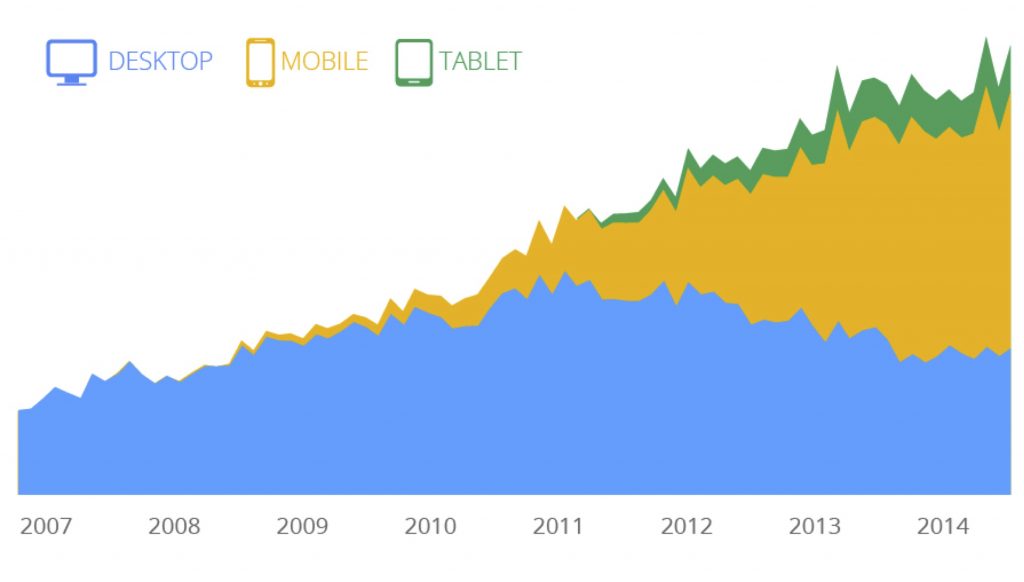

Adaptive content isn’t the only reason to do structured content, but it is the most pressing. As Google’s graph from a couple of years ago shows, mobile users are quickly becoming the primary users of digital content. Responsive design is no longer optional. Adaptive content is also quickly becoming standard operating procedure for content marketers.

Challenges to structured content publishing

As good as it sounds, structured content is hard for a couple of reasons.

1. Semantic tagging

The same piece of content might be highly relevant in one context and irrelevant in another. So you can’t just move content modules around without knowing for what contexts the modules were originally written. If different people have access to change module location or order, this means tagging them not just for their structure (e.g. pull quote), semantics (e.g. topic), device (e.g. phone body paragraph one), but also for their context (e.g. intended audience, buy cycle state). That’s a lot of tagging. It gets even more complex when you add the need to tag each module with codes for metrics, especially if you want to test them in different locations within a page.

You can limit how much tagging you need if you just want to make your content more adaptive. One article for three devices is not that hard, especially if you’re committed to testing. But if you want to reuse some of the components of that article in other places, you need a lot of tagging. An example is wanting to use a pull quote from an article in a related case study. Most organizations that want adaptive content also want this kind of reuse.

In my experience, the weak links in content publishing are taxonomy and tagging. The taxonomies are the structured lists of labels we give things, including things like product, topic, intended audience, buy cycle state, and other metadata. Tags are either metadata or schema markup elements we assign to content modules. It is difficult to get the right values in your taxonomies, especially if your business changes often. Even if you have the right values in your taxonomies, getting authors and editors to use them correctly is a huge challenge. I’m not going to solve it here. Just note that you probably need to invest more in this area if you want effective adaptive content.

2. Writing for structure

Most authors and editors like to write a whole blog post or article, rather than a bunch of components that could be assembled into an article or blog post (or both), for any device. We are trained to work on transitions between paragraphs, for example. In modular content, most paragraphs are their own modules of one sort or other. So each paragraph needs to stand on its own, or together with any other relevant paragraph. Learning to write for structure can take a long time. While your authors and editors are descending the learning curve, your adaptive content will not be as effective as you might hope.

There are ways to accelerate the learning curve. One way is to have your writers work in teams. Rather than being responsible for a whole piece, perhaps one writer is just responsible for value propositions, for example. The assembly-line model might not be as fun for the authors, but it can produce better results. At the very least, peer review can catch a lot of contextual problems with modules that aren’t as portable as they should be.

Next steps:

If you haven’t started transforming your content production system for structured content, now is the time to start. We write about this at some length in the book. That will have to suffice for the time being. But just know that few do this well today. So whatever you do in this direction will give you a leg up on your competition.